Scientists have just found the world's longest chain of volcanoes on a continent, hiding in plain sight.

The newly discovered Australian volcano chain isn't a complete surprise, though: Geologists have long known of small, separate chains of volcanic activity on the island continent. However, new research reveals a hidden hotspot once churned beneath regions with no signs of surface volcanism, connecting these separate strings of volcanoes into one megachain.

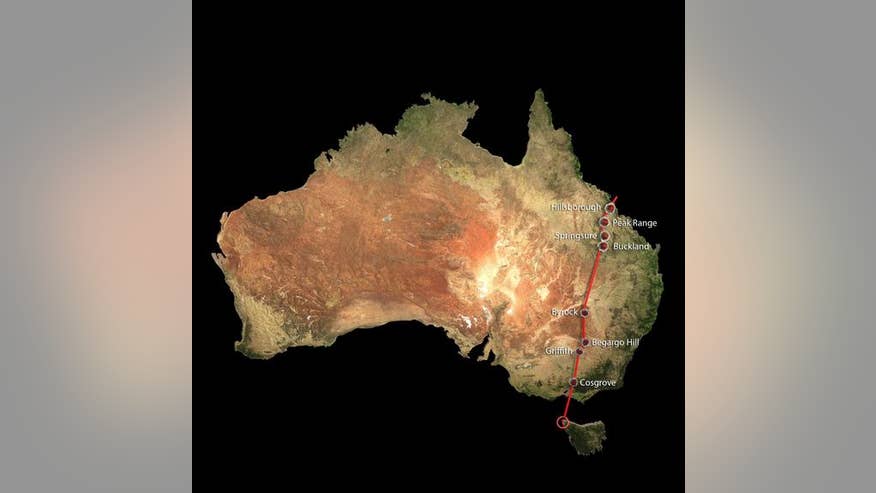

That 1,240-mile-long chain of fire spanned most of eastern Australia, from Hillsborough in the north, where rainforest meets the Great Barrier Reef, to the island of Tasmania in the south.

"The track is nearly three times the length of the famous Yellowstone hotspot track on the North American continent," Rhodri Davies, an earth scientist at Australian National University, said in a statement. [See Amazing Photos of the World's Wild Volcanoes]

String of volcanoes

Scientists had long known that four separate tracks of past volcanic activity fringed the eastern portion of Australia, with each showing distinctive signs of past volcanic activity, from vast lava fields to fields awash in a volcanic mineral called leucitite that's dark gray to black in color. Some of these regions were separated by hundreds of miles, leading geologists to think the areas weren't connected.

But Davies and his colleagues suspected that the Australian volcanism had a common source: a mantle plume that melted the crust as the Australian plate inched northward over millions of years. (Whereas many volcanoes form at the boundaries of tectonic plates, where hot magma seeps up through fissures in the Earth, others form when mantle plumes, or hot jets of magma, at the boundary between the mantle and Earth's core reach the surface.)

To bolster their hypothesis, Davis and his colleagues used the fraction of radioactive argon isotopes (versions of argon with different atomic weights) to estimate when volcanic activity first appeared in each of these regions. They combined this data with past work showing how the Australian plate had moved over the millennia. From this information, they could estimate where and when volcanism affected certain regions.

The team found that the same hotspot, likely from a mantle plume, was responsible for all of the volcanic activity crossing eastern Australia. The new volcanic chain, which the team dubbed the Cosgrove volcanic track, was formed between 9 million and 33 million years ago. (None of the volcanoes on Australia's mainland have been active during the recen past.)

However, there are large gaps in volcanic activity on the surface of this track. To understand why, the team modeled the thickness of the lithosphere, the stiff layer that forms the upper mantle and Earth's crust.